A little while ago my friend Max gave me his WikiReader to play around with. At the time I didn’t really know what to make of the little white square-ish device he handed me, but he said something along the lines of “It’s got all the top Wikipedia articles on it and some company made a dedicated electronic device for reading Wikipedia before that kind of thing was cool again. Just take it and play around with it, you’ll think it’s neat.” Turns out Max was right, I DO think it’s neat! The WikiReader isn’t the greatest way of reading Wikipedia — it’s not even the best way of reading Wikipedia offline — but it is a rare example of a now unsupported electronic device that has aged quite gracefully.

Wiki What Now?

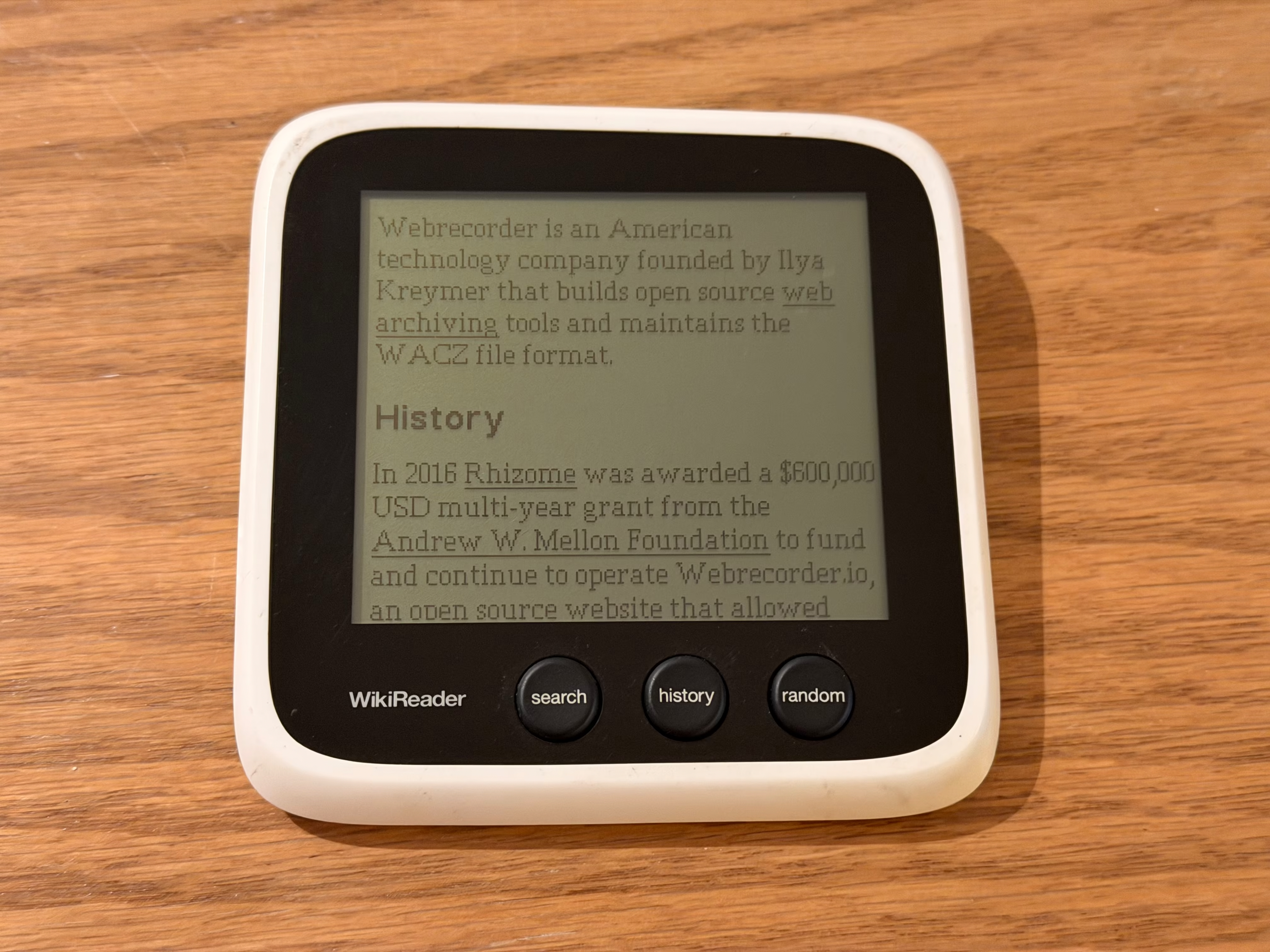

The WikiReader is a standalone gadget that lets you read Wikipedia articles. It has three buttons (pictured above) and a monochromatic LCD touch screen for keyboard entry, scrolling through pages, and navigating with links. It’s powered by two AAA batteries and loads data from a microSD card. It’s a pretty simple device, however you imagine it working based on the photo is probably mostly correct.

While any piece of hardware integration is an achievement, the coolest part of the WikiReader is handing it to somebody else, telling them “this device from 2010 has the entirety of Wikipedia on it”, and watching them try to figure out how that works. In the age of ‘the cloud’, the inner workings of the web are quite abstract for most people: they ask for content from the void and it is returned on their screen. In our modern ‘frictionless’ world, one needn’t concern themselves with where the data actually comes from.

The WikiReader reminds us that it is also still possible to serve vast quantities of information directly from the device in your palm. There are no subscriptions required, it doesn’t need an internet connection, you don’t need to sign in with Google, WikiReader doesn’t collect cookies, there are no terms and conditions, there is no privacy policy. You just turn it on and it does the thing you want it to do.

So Where Can I Buy One?

Check Ebay maybe? Pandigital (the company that produced the device) went bankrupt in 2012, but still exists in some form selling printers today? Their previous work in the e-reader field seems to be missing from their website as of 2025.

If you already have one though, you can bring it into the modern era!

Updating Your WikiReader in 2025

Before going under, Pandigital did the responsible thing and open sourced the entire codebase on GitHub which was an excellent move! Developer Stephen Wood has forked the original repo and created an updated, Dockerized build script to take dumps directly from Wikipedia and convert them to WikiReader compatible text files. Reddit user /u/geoffwolf98 has a similar script and kindly converts Kiwix files to WikiReader-compatible data dumps, uploading the results to the Internet Archive for everyone to use (here’s one from August 2025). If you’re looking at this post in the future, check out the WikiReader subreddit, there will probably be a more recent one there.

As for how to actually update your device: grab a 64GB microSD card and format it as FAT32. Download and copy the latest dump of the filesystem from Internet Archive to the SD card. Finally, copy the enpedia folder from the updated WikiReader download above to the root of the SD card, and get reading!

Offline Wikipedia in the Modern Age

Dedicated devices are charming, but if you’ve ever wanted to host an offline archive of cool openly available knowledge Kiwix is likely the best way to do this today! Kiwix is a web archive player for their ZIM file format (which shares a lot of similarities with Webrecorder’s WACZ except for that it doesn’t rely on WARC records… but hey, sometimes being different is fun). More importantly however, they provide pre-packaged downloads of Wikipedia in multiple languages, various other Mediawiki sites, and many popular game wikis and open source software docs — handy for working while flying, though lots of airlines have wifi at this point. The future is now!

It takes only a few minutes to download the Kiwix Reader app for your platform of choice, torrent some ZIM files from their library, and get reading! If you want to deploy this on a network you can also run Kiwix Server to run local copies of any ZIM packaged content for others.

Personally I run Kiwix Server on TrueNAS and keep a copy of English Wikipedia (with images) around because it makes me happy. Dedicating ~140GB of space on my server seems like a small price to pay for me to know that I’ll likely always be able to access some of the best free knowledge humanity has ever collected whenever I want.

Hardware Lessons from the WikiReader

There’s a few bits of product strategy that I wish hardware manufacturers would employ that are exemplified in this device.

1. Try to keep your device useful after you go bankrupt

Max’s WikiReader is working better today than it ever did at launch! Because it adheres to local-first software principles and functions completely offline, there were no issues when the parent company went under. This is in stark contrast to Spotify’s ‘Car Thing’ which Spotify recommends throwing away1 or the Humane AI Pin (where customers were at least issued refunds before their devices were purposefully bricked and the company’s IP was sold to Hewlett Packard).

Don’t create manufactured garbage.

2. Make calculated bets on longevity when integrating tech

This device bet on user-replaceable AAA batteries instead of integrated cells and microSD cards over soldered flash. If the batteries degrade, it is usually reasonably easy to clean off any corrosion or replace the pads. Meanwhile, microSD cards have only gotten larger and cheaper as time has gone on. It cost me 12 bucks to upgrade this one with a 64GB SD card!

I’m not saying that you need to use swappable batteries for everything of course, but if you’re integrating rechargeable ones, try to ensure that replacing them won’t be a complete pain in the ass for your customers — rechargeable batteries are consumable components after all.

3. If you make money by selling hardware, consider open sourcing your software

The only reason I was able to do any of this is because there was a clear path for some well intentioned folks with the requisite skills to make their tech work for them. Could the devs I mentioned above have reverse engineered the file format? Probably! Is that more work? Absolutely!

The latter is a troubling status quo in the smart home space. Companies will sell locked down hardware products and some nerd will spend ungodly amounts of time reverse engineering Home Assistant compatible firmware for their air purifier because they just want it to talk to everything else without a dumb proprietary app.2 Proprietary software for your otherwise standalone hardware device signs its death warrant for the day you stop maintaining it.

Give your customers the means to maintain to the thing they bought from you!

Footnotes

-

Do you own a Car Thing? Don’t just throw it out! You can make it do cool stuff again with Desk Thing! ↩

-

Regarding smart home stuff, I prefer to rely on “some nerd on the internet” over a large company every time. The maintenance and longevity standards that the open source smart home community has are pretty much always higher than what corporate America is willing to provide. ↩